A Sense of Place

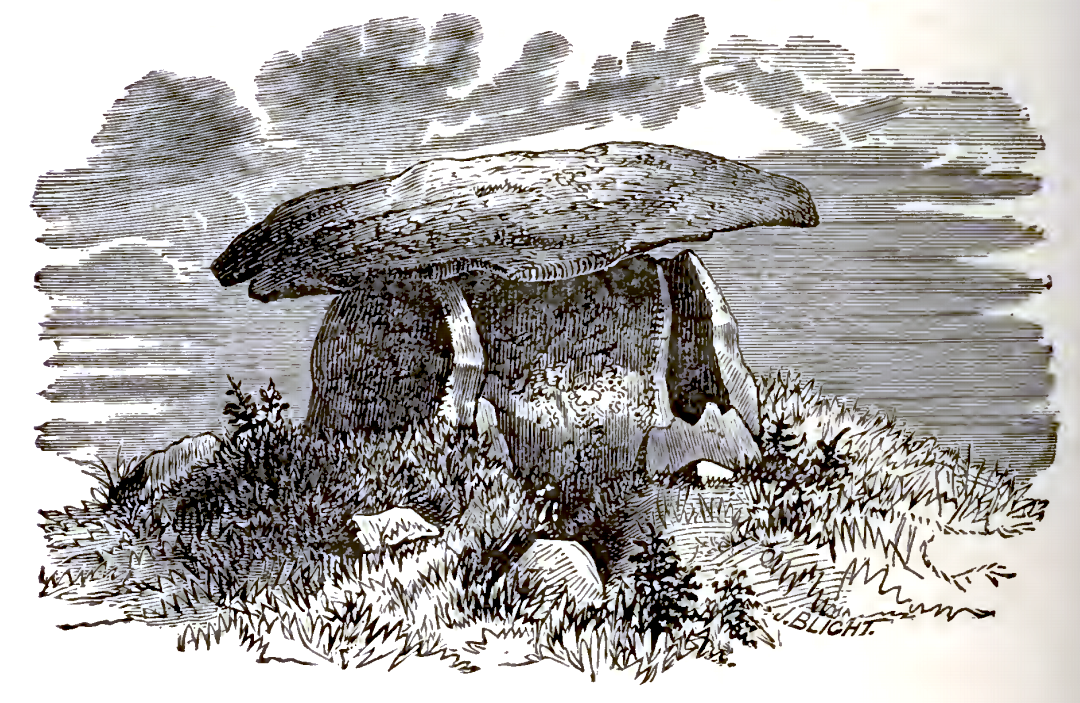

We tramped in total darkness across the Penwith moor in search of Chûn Quoit, the ancient remains of a round barrow – the final resting place of some long-forgotten tribal chieftain. To anyone who hasn’t seen one, a quoit – the Cornish name for a cromlech – is a structure that calls to mind the offspring of a colossal stone mushroom and a 12 foot milking stool. Four granite ‘legs’, each a slab of 20 tons, support a substantial capstone, all of which would once been hidden under a mound of earth. With its bare bones revealed there is an elemental quality about the structure – even on a bright day it has an austere menace that would put the willies up Boris Karloff, but picked out in torchlight against the midnight sky it was quite terrifying. The terror was all the more real because the night before, in a well-lit, warm and comfortable house, I had volunteered to sleep in it in the name of cognitive archaeology.

The idea was to record my dreams and to analyse them to see if they contained any interesting symbolism – symbolism which would hint at some hidden aspect of the place. My guide, companion and the man who would note down my nocturnal ravings was Paul Devereux, author of a slew of books on earth mysteries that treat the fluffy air-head dogmas of new age thinking with the skepticism they deserve in favour of original research into the unanswered questions raised at the fringes of science, culture and anthropology.

Paul happened to be a neighbour of mine and we shared a common interest, though my investigations of the fortean world were shambling and shallow in comparison. Only a couple of nights before he had handed me a sachet of what looked like sweepings from the barn floor to make up into a cold tea. The sawdust and twig infusion claimed that it would open up the third eye and help me to dream of interesting things but it tasted as bad as it looked and my third eye remained firmly shut, possibly in disgust.

We picked our way over the rocky terrain that lay between our car and the quoit, determined to keep to the well worn path. This part of Cornwall was mined for tin ore until the nineteenth century and some of the miners moonlighted on their own undocumented tunnels to make ends meet. As a consequence, Penwith has more holes in it than cartoon cheese – a fact that is underlined periodically when a cow goes hurtling down a mine shaft or somebody’s driveway unexpectedly disappears into the abyss.

After a quarter of an hour we arrived at Chûn and I crawled through the narrow opening.

To say the chamber was dank and claustrophobic doesn’t do it justice. Imagine a very small tent made out of five slabs of rock leaning on one another in a house of cards configuration, except that the cards weigh as much as 20 tons each. Rounded fragments of granite, rooted in the floor of the chamber, found hitherto undiscovered vertebrae which ever way I shifted myself to get comfortable, but it was the gnawing sense of ill-ease that was the real enemy of rest. Outside the chamber, the sky was as black as a bin liner, but inside, my mood had darkened to match.

Paul explained what the plan for the evening was. I was to doze off and be rudely awoken once I had begun to dream, at which point I would be expected to babble it all out before it had a chance to scuttle away into the night or my conscious mind made too much sense of it.

“But how will you know when I’m dreaming?”

“You’ll go into REM sleep – and I’ll be able to pick up your rapid eye movements with this”, said Paul, as he dug into his knapsack.

I half expected him to present me with a little scientific gizmo of some kind – maybe an electrode for my temple, a sensor on the end of a colour-coded wire or a coiled cable that led to an adapted moped helmet. So I was quite disappointed when he pulled out a bicycle lamp – a rear lamp which, he informed me, would enable him to catch my eye movements without disturbing me unduly.

It took another hour for my mood to melt from its agitated state. I was just drifting off peacefully, snatching the first images of the night, feeling the hypnogogic whirl into the vortex of dreams when I was pulled back from the brink of the plughole by the glow of a bicycle lamp in my eyes. After gabbling out some inconsequential mutterings, it was clear that we were all a little disappointed. We went home, exhausted, with no concrete dreams and only the memory of dark menace to console us.

From

Naenia Cornubia

A descriptive essay illustrative of the sepulchres and funereal customs of the early inhabitants of the County of Cornwall.William Copeland Borlase, BA, FSA

CHYWOONE CROMLECH

The most perfect and compact Cromlech in Cornwall is now to be described. It is situated on the high ground that extends in a northerly and westerly direction from the remarkable megalithic fortification of Chywoone or Chuun, in the parish of Morvah.The " Quoit" itself, which, seen from a distance, looks much like a mushroom, is distant just 260 paces from the gateway of the castle; and about the same distance on the other side of it, in the tenement of Keigwin, is a barrow containing a deep oblong Kist-Vaen, long since rifled, and now buried in furze.

Thinking this monument the most worthy of a careful investigation of all the Cromlechs in the neighbourhood, the author proceeded to explore it in the summer of 1871, with a view to determine, if possible, the method and means of erection in the case of such structures in general.

blog comments powered by Disqus