Setting Your Boundaries

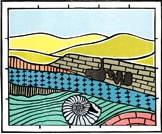

There are hundreds of miles of Bronze Age dykes in Britain, although not many of them are as impressive as the deep ditch and high rampart of Bokerley Dyke - a feature which has been shown to predate the Roman occupation. Not much is known of their use as prehistoric borders except that the smaller dykes are believed to be property, rather than territorial, boundaries. Bokerley Dyke’s survival since the Bronze Age is the outcome of its continual use for thousands of years; its upkeep, modification, reiteration and reinvention are all factors in its continued existence in the 21st century and you don’t have to look far to see what an achievement that is.

Looking south from the crown of the dyke, the landscape of East Dorset re-asserts the consensus view of post-war countryside; the familiar layout of arable and dairy, of copses that cling to the hillside and of lone trees apparently stranded at the centre of fields. Tramlines of tractor tracks skirt around each oak or ash like decorative ripples around an island map. In a large field, a solitary tree is often all that is left of a grubbed-up hedge, but here there is a line of them, cast adrift from the field’s edge on a long green island that joins together a pair of Neolithic long barrows.

The barrows are at the northern end of what may turn out to be an even older boundary than Bokerley Dyke. The Dorset Cursus is an enclosed linear earthwork up to 100 metres wide that runs for ten kilometres to the south west – by far the largest of at least 150 similar ancient monuments all over Britain. Nobody knows what purposes they served. Even the most popular theory, that they were processional walkways, doesn’t ring true because their design often included obstacles like boggy valleys and rivers and would make for the most ungraceful procession imaginable.

The location of a cursus often displays a preoccupation with the landscape itself, particularly rivers, but also on the transition from one kind of geology to another. There is some suggestion that they may also be figurative boundaries – perhaps an enclosed limbo between ‘wild’ and ‘domesticated’ land, or as at the Stonehenge cursus, between the landscape of the dead and that of the living. The Dorset Cursus crosses land between tributaries of the Hampshire Avon and those of the Stour, running roughly along the natural spring line.

As far as archeology has been able to tell, the Neolithic in Britain marked the dawn of a spirituality rooted in the relationship between the sky and the land, a practical theology that successfully linked astronomical events to agricultural practise. Our first artificial boundaries may have sought to mark out different kinds of land according to those beliefs, but by the Bronze Age, these sacred lines were dismissed in favour of more earthly divisions.

A Sense of Place

We tramped in total darkness across the Penwith moor in search of Chûn Quoit, the ancient remains of a round barrow – the final resting place of some long-forgotten tribal chieftain. To anyone who hasn’t seen one, a quoit – the Cornish name for a cromlech – is a structure that calls to mind the offspring of a colossal stone mushroom and a 12 foot milking stool. Four granite ‘legs’, each a slab of 20 tons, support a substantial capstone, all of which would once been hidden under a mound of earth. With its bare bones revealed there is an elemental quality about the structure – even on a bright day it has an austere menace that would put the willies up Boris Karloff, but picked out in torchlight against the midnight sky it was quite terrifying. The terror was all the more real because the night before, in a well-lit, warm and comfortable house, I had volunteered to sleep in it in the name of cognitive archaeology.

The idea was to record my dreams and to analyse them to see if they contained any interesting symbolism – symbolism which would hint at some hidden aspect of the place. My guide, companion and the man who would note down my nocturnal ravings was Paul Devereux, author of a slew of books on earth mysteries that treat the fluffy air-head dogmas of new age thinking with the skepticism they deserve in favour of original research into the unanswered questions raised at the fringes of science, culture and anthropology.

Paul happened to be a neighbour of mine and we shared a common interest, though my investigations of the fortean world were shambling and shallow in comparison. Only a couple of nights before he had handed me a sachet of what looked like sweepings from the barn floor to make up into a cold tea. The sawdust and twig infusion claimed that it would open up the third eye and help me to dream of interesting things but it tasted as bad as it looked and my third eye remained firmly shut, possibly in disgust.

We picked our way over the rocky terrain that lay between our car and the quoit, determined to keep to the well worn path. This part of Cornwall was mined for tin ore until the nineteenth century and some of the miners moonlighted on their own undocumented tunnels to make ends meet. As a consequence, Penwith has more holes in it than cartoon cheese – a fact that is underlined periodically when a cow goes hurtling down a mine shaft or somebody’s driveway unexpectedly disappears into the abyss.

After a quarter of an hour we arrived at Chûn and I crawled through the narrow opening.

To say the chamber was dank and claustrophobic doesn’t do it justice. Imagine a very small tent made out of five slabs of rock leaning on one another in a house of cards configuration, except that the cards weigh as much as 20 tons each. Rounded fragments of granite, rooted in the floor of the chamber, found hitherto undiscovered vertebrae which ever way I shifted myself to get comfortable, but it was the gnawing sense of ill-ease that was the real enemy of rest. Outside the chamber, the sky was as black as a bin liner, but inside, my mood had darkened to match.

Paul explained what the plan for the evening was. I was to doze off and be rudely awoken once I had begun to dream, at which point I would be expected to babble it all out before it had a chance to scuttle away into the night or my conscious mind made too much sense of it.

“But how will you know when I’m dreaming?”

“You’ll go into REM sleep – and I’ll be able to pick up your rapid eye movements with this”, said Paul, as he dug into his knapsack.

I half expected him to present me with a little scientific gizmo of some kind – maybe an electrode for my temple, a sensor on the end of a colour-coded wire or a coiled cable that led to an adapted moped helmet. So I was quite disappointed when he pulled out a bicycle lamp – a rear lamp which, he informed me, would enable him to catch my eye movements without disturbing me unduly.

It took another hour for my mood to melt from its agitated state. I was just drifting off peacefully, snatching the first images of the night, feeling the hypnogogic whirl into the vortex of dreams when I was pulled back from the brink of the plughole by the glow of a bicycle lamp in my eyes. After gabbling out some inconsequential mutterings, it was clear that we were all a little disappointed. We went home, exhausted, with no concrete dreams and only the memory of dark menace to console us.

From

Naenia Cornubia

A descriptive essay illustrative of the sepulchres and funereal customs of the early inhabitants of the County of Cornwall.William Copeland Borlase, BA, FSA

CHYWOONE CROMLECH

The most perfect and compact Cromlech in Cornwall is now to be described. It is situated on the high ground that extends in a northerly and westerly direction from the remarkable megalithic fortification of Chywoone or Chuun, in the parish of Morvah.The " Quoit" itself, which, seen from a distance, looks much like a mushroom, is distant just 260 paces from the gateway of the castle; and about the same distance on the other side of it, in the tenement of Keigwin, is a barrow containing a deep oblong Kist-Vaen, long since rifled, and now buried in furze.

Thinking this monument the most worthy of a careful investigation of all the Cromlechs in the neighbourhood, the author proceeded to explore it in the summer of 1871, with a view to determine, if possible, the method and means of erection in the case of such structures in general.

Layby of the Week: Knockan Crag

View Larger Map

Staying in Scotland – and not so far from last week’s layby on the A837 to Lochinver – another worthwhile stop-off on the west coast Rock Route designated by Scottish Natural Heritage, the Knockan Crag National Nature Reserve car park, near Elphin on the A835.

The Knockan Crag NNR is amazing. An unmanned visitor centre open all-hours, all-year with information and interactive displays on the landscape and geology of the area and two circular trails for different abilities, a car park and toilets. There are beautiful rock sculptures in the, frankly, prehistoric landscape and glorious views of Loch and Lochans stretching out at your feet. There are plenty of steps, but there's also a wheelchair/pushchair-friendly path to the Rock Room with its hands-on displays and touch-screen computer.

It's all in honour of tectonic forces that were strong enough to weld continents together, create the mountains and slide a huge block of ancient landscape dozens of kilometres over the top of younger rocks. All of that happened at Knockan Crag.

The Rock Room is a short, easy walk from the car park and it comes recommended.

Layby of the Week: Assynt

View Larger Map

The Lewisian Gneiss here is between two and three billion years old and is all that survives in Britain of our Canadian connection, when this part of Scotland was also part of the ancient nucleus of North America. The policeman’s helmet mountain on the horizon is Suilven, about 4 miles to the south east of this layby and is made of comparatively young (only one billion-year-old) Torridonian sandstone.

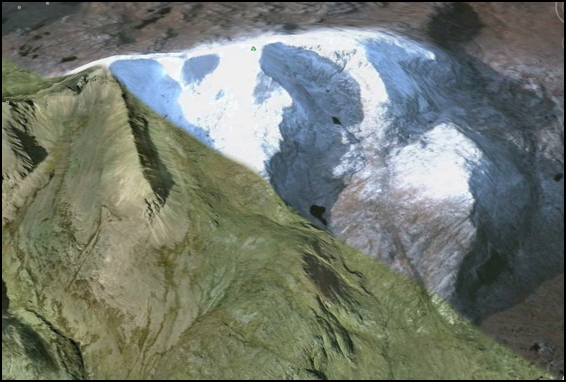

Northwest Highlands Google Earth fly-by

The complete tour takes about 17 minutes; if you are desk-bound for lunch, we’d recommend chomping your sandwiches as the Northwest Highlands float by underneath for a more relaxing break than might usually be the case.

We’ve kept it simple for now - no narration or music to accompany the scenery, but we might get bold in the future. We hope you enjoy the view.

Download Seventeen minutes in the Northwest Highlands.

Google MountainView 1

View Larger Map

This view, near the top of the winding lane that follows the Watendlath Beck from Derwent Water up to its eponymous Tarn, complete with lay-by encapsulates everything that is wonderful about the Lake District the glaciers left behind.

English Riviera Geopark film

Solstice special:

The Day that Stonehenge Disappeared

I struggle to keep up on an unexpectedly warm autumn evening as I galumph my way across rough downland in pursuit of a tour guide. Pat Shelley is leading me from one location which boasts a million visitors a year to another that only a few hundred manage to see. I’m grateful for his expertise because across the hummock-strewn field ahead lies Stonehenge Cursus, a curious feature every bit as enigmatic as the main attraction.

I had thought that getting off the trampled track so close to the well-beaten A303 would be a near impossibility. To do so within sight of Stonehenge which is, after all, the acme of tourist attractions, would be harder still. So, when Shelley - a local tour guide I had met the year before - got in contact offering a social drink and an evening around the stone circle, I have to say I was very much looking forward to the beer.

Shelley’s enthusiasm for, and knowledge of, Stonehenge is unsurpassed. He’s spent years showing tourists around the area and has helped out on many archaeological digs, a background that helps him synthesize all the latest theories and ongoing work around the monument, seemingly at the drop of a hat. He wanted to show me something that very few tourists get a grip on - that the landscape around Stonehenge is every bit as important as the stones themselves. Recent archaeological work has uncovered many links between it and other monuments - among them, Durrington Walls and Woodhenge to the east and ‘Bluestonehenge’, discovered earlier this year by the Stonehenge Riverside Project next to the River Avon - and these links suggest that the Stonehenge Landscape was, indeed, huge.

The Stonehenge Cursus, recently dated to between 3630 and 3375 BC, is nearly two miles long and ranges from three to five hundred feet in width. On the Ordnance Survey map it appears as a prominent rectilinear feature amongst the blunderbuss grapeshot of Neolithic and Bronze Age barrows that lie spattered across the Wiltshire landscape. So it comes as a shock that the Cursus is barely perceptible on the ground - an indeterminate ditch and bank arrangement which only resolves itself as a wide gap cut through a hangar of trees at its western end.

After a few moments of disappointment, I adjust my expectations and imagine the sheer scale of the endeavour. I remind myself that the most spectacular forms on the planet are often ones for which no particular purpose springs to mind, enchanted as we are by the brute pointlessness of ancient lines on the landscape - lines which can only really be appreciated from above. Indeed, nobody has the slightest idea what it or any of the hundred or so similar features in Britain are actually for; all explanation defaults to a mumble of ‘ritual use’, which, Shelley informs me, is an archaeological euphemism for ‘we don’t really know’.

One thing is certain, however: apart from what remains of the outline of this great human mark, there is precious little archaeology actually on it. Given our ancestors’ implied lack of care with their coins, combs, tools and artefacts, it is odd that a huge area that probably took thousands of man hours to construct should be so bereft of human clutter. It is almost as if it had been kept consciously clean.

While I mumble about the minimalist Neolithic to myself, my guide takes off across the field, promising to show me something that I would never forget - as if in compensation for showing me something that I could barely see.

As anyone who has spent a merry hour or two queuing on the A303 will tell you, Stonehenge is a prominent feature. While it melts sympathetically into views of its immediate vicinity from the middle distance, at close quarters you just can’t take your eye off the thing: it dominates the landscape and, moreover, it seems to be following me around now, forever in my peripheral vision in a way I imagine it must have been for our ancestors. I catch up with my guide at the foot of a low eminence, turn around and it has vanished - which is disturbing, given that it is only a few hundred yards away.

We are on The Avenue, a grand, curving earthwork ‘road’ almost two miles long that seems to be a processional walkway from the River Avon to the henge. Shelley is motioning to me to walk up towards the circle and, as I do, I can’t help gasping as the familiar outline of Stonehenge reappears, rising above the grass and thistles in a strange inversion of druidic tradition. It suddenly becomes clear that Stonehenge is more than a familiar pile of stones, but part of a larger landscape, even a stage-managed experience. Like the best theatre, Stonehenge can still surprise.

Layby of the Week: Llyn Cwm Bychan

View Larger Map

If your browser does not support Google Earth’s plug-in, you’re out of luck if you’re waiting for the Google Street car to arrive - this spot is simply too remote. Fortunately, the British Landscape Club have got there before you.

At the head of a remote valley and at the heart of the Snowdonia National Park, this Welsh lake sits at the centre of an eroded away dome - the Harlech Dome - of buckled rock that once bridged Snowdon in the north to Cader Idris in the south.

The lake is fed by the Afon Artro stream, the valley of which provides a mean transport corridor, enough for a hairy single track most of the way up from the village of Llanbedr on the coast road near Harlech. There’s a full account of its wonders in the Club manual, The Lie of the Land by Ian Vince, but all you need to know is that there’s a car park, a portaloo and moments of unfettered wilderness and blissful peace around this amazing spot.

Layby of the Week: Silbury Hill

View Larger Map

If your browser does not support Google Earth’s plug-in, here’s a real view of Silbury Hill, taken from just down the road by the Google Street Maps car.

View Larger Map

Either way, it’s an impressive structure - Europe’s largest man-made hill, it rivals some Egyptian pyramids in size and was built over successive generations from about 2400 BC. It is located in a landscape of dip and scarp, gently undulating chalk downs occasionally punctuated by imposing escarpments.

The recently synthesized view is that Silbury Hill, successive excavations of which have yielded no burials, was constantly tinkered with by our Neolithic ancestors as a kind of devotional labour, perhaps commemorating their ancestors who laboured for thousands of years building a ritual landscape in and around nearby Avebury, the site of the largest henge in the world - itself a devotional labour of epic proportions.

There’s a layby and viewing area a little to the west on the A4.

A view of a tiny part of the henge at Avebury.

View Larger Map

An aerial view.

Layby of the week: Under Mam Tor

View Larger Map

Mam Tor is also known as the shivering mountain as a result of this instability. What's left of the road is still making its way down the valley.

Famous landscapes:

Gold Hill, Shaftesbury, Dorset

The views look south towards a landscape made from Cretaceous chalk and greensand and older mudstones and siltstones from the Jurassic period. To the west of Shaftesbury the Jurassic continues - with many of the same limestones that are found in the Midlands cropping up, lending the area its Cotswolds atmosphere.

Lay-by of the week: Autumn Leaves

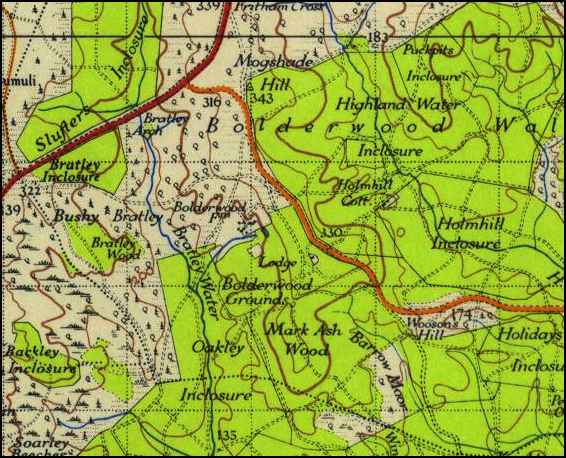

A special lay-by of the week this week from Bolderwood in the New Forest; not so much a lay-by as an interesting place to park, courtesy of the Forestry Commission.

View Larger Map

Ordnance Survey 1 Inch New Popular Edition 1945

During the summer months, the wildly interesting information kiosk (run-of-the-mill town centre TICs please take note) is open and on a busy weekend when the weather is nice you will often find an ice cream van parked up. But all of that is moot, because a short walk from the car park is a deer viewing platform - from where you may be lucky enough to spot a Red Stag or a group of Roe Bucks - like the picture below.

It’s also a timely reminder, as autumn passes into winter, of the importance of trees in the landscape, both from an aesthetic and functional view. Our forests are rich habitats that, like all woodland the world over, need to be managed and preserved not only for the good of some abstract ecological notion, but also because indiscriminate felling or management of them for anything other than their natural value is madness. The Coalition Government has recently announced it is to sell off up to half of our national forests. Not only would this put habitats and wildlife in severe danger, but it wouldn’t even raise very much money - making it all look less like a response to a financial crisis and more like an ideologically-sponsored privatisation; less like selling the family silver, more like putting our back garden up for sale. Anyone who cares about our landscape is strongly urged to join over 35,000 signatories (in the first week alone) and sign the 38 Degrees petition now - maybe they’ll think again when they see the numbers.

Lay-by of the week:

The Cow and Calf Rocks, Ilkley Moor

Overnight, a thick fog descended, but 35 people dutifully turned up to follow me around the Cow and Calf anyway, despite visibility beyond the end of one’s arms becoming difficult, so this week’s lay-by of the week is dedicated to the helpful folk of Ilkley and its environs.

View Larger Map

NB, For aesthetic reasons, the Googlecar is a little below the Cow and Calf car park in this shot.

Lay-by of the week: Loch Lubnaig

“When you drive up out of the central belt, climb up into the hills and drive alongside the loch here you just have to pull in at the parking / picnic spot, and take a good long look at the loch. The water can go glassy flat and reflects like a mirror. Terrific.”

View Larger Map

Night time views - Salisbury

What buildings there were nestling in the valleys would have had greater significance - especially after a long journey or pilgrimage across the country. I hope that this view of Salisbury Cathedral - which for hundreds of years would have been the tallest building in the western world - captures something of the awe a long-distance medieval traveller would have felt 700 years or so ago. By removing the detail of the town that has grown up around it, with its ring road, modern development and other 20th and 21st Century clutter and even with the housing development in the foreground, this magnificent old cathedral still takes your breath away.

Lay-by of the week:

Porlock Bay and Selworthy

View Larger Map

If you’re driving on the A39, the road that connects the main towns of North Somerset and Devon, chances are you’re not getting anywhere very fast, so why not relax and make a detour to the village of Selworthy. This is the church car park in the village - rotate the panorama a little for a view of Selworthy’s beautiful white church.

View Larger Map

More pictures from trains

I’ve added a few more photos to the gallery of landscapes taken from trains. It seems like an unconventional way of capturing scraps of scenery as they zoom by and an excellent mental diversion when the novelty of getting out and about wears thin which, as any commuter on Britain’s railways will tell you, can be quite quick.

If you have some train pictures you want to share, feel free to add some in the comments below.

Lay-bys of the week:

Cape Cornwall and Lizard Point

The text book definition of a cape, by the way, is a promontory where two major bodies of water meet - in this case the Atlantic and St George's Channel. Since those nineteenth century OS men declared Lands End as further out in the ocean it is arguably where the waters meet rather than Cape Cornwall, but the name stuck anyway.

View Larger Map

Meanwhile, there’s no such controversy about Lizard Point, mainland Britain’s most southerly spot. There’s a National Trust car park there as well and a bonus collection of sheds that sell souvenirs carved from the local rock. This rock, serpentine, is metamorphic in origin, 400 million years or so old, and an excellent example of a bit of oceanic crust that has unaccountably slid over the top of a piece of continent (it almost always slides under when the two collide).

You might like a cup of tea, while you contemplate that and, besides one of the souvenir sheds, lies the cafe with the best view in all of Cornwall (below). It’s always busy in the season and it’s always worth the wait. You may even be fortunate enough to see a couple of Cornish Choughs wheeling in the sky, failing that you can stare at the cliff that rings with the sound of Jackdaws and Kittiwake and hope to catch a glimpse of a Peregrine or two.

View Larger Map

Monstrous Carbuncle

But one of those towns – and not just any old market town, but Dorset’s county town – will never be the same again. For Dorchester has been tainted by its association with the monstrous carbuncle that is HRH Prince Charles’ Poundbury or, to give it a name accidentally arrived at in a Freudian slip of the tongue, Poundland.

View Monstrous Carbuncle in a larger map

This grotesque and repulsive display of architectural pus sits on the eastern horizon as you approach Dorchester from the west. The awful buildings infect the surrounding landscape with their weak-minded parody of a passing resemblance to a rough similarity to a half-remembered Tuscan hill-top village. Who-ever presided over this inferior and wholly unaesthetic effort should be shot through the lungs with high-velocity 2H pencils.

Some of Poundbury is well-executed, even if it is obviously the work of a cobwebbed mind. While the Duke of Cornwall proclaims his love of traditional vernacular architecture and actually has interesting and useful ideas about the sustainability of communities, his biggest showcase looks like a malformed bleb from the side of the A35.

Lay-by of the week: Askerswell from the A35

View Larger Map

One bright and crisp winters day a short breath after Christmas, we were driving through Dorset as we made our way back from Cornwall. The journey was quite familiar to me and I had never given it much thought. A couple of years before, I had come the closest to thinking deeply about travel when two friends and I covered the same ground as part of an epic, 15 mph journey across England in an electric milk float but, crucially we had picked a different route for this stretch.

I was on the A35, a murderously busy road we had escaped from while on the float - a quick turn-off that happened to land us in Arcadia, an enchanted valley near Little Bredy trapped somewhere between dusk and the early 1950s. It was the encapsulation of pastoral beauty and I will remember the scene for ever.

As so often happens in Britain though, by catching one thing, you miss another and the A35 - for all its homicidal ways - is the scene of something on a par with our Dorset Arcadia but in a different way. The stretch of it we avoided, between Dorchester and Bridport, affords awe-inspiring views of the lumpy, bumpy Dorsetshire hills, the festival of buxom hummocks that made it into the introduction to The Lie of the Land.

As ever, all attempts to capture such grandeur on a soul-less semiconductor fail miserably. I’ve taken my version of the Google Street View, but the best stuff is on the other side of the road when the road reaches its height and the views over the Dorset coast are breathtaking. You really have to see the view for yourself.

Lay-by of the week: Danebury hillfort

View Larger Map

Danebury is a magnificent Iron Age hillfort a few miles north of Stockbridge. There are two car-parks, the lower of which is clearly visible from the Google Street View car, but visitors can make their way further up the drive to a second parking area partially under the cover of trees. It’s then a short, moderately stretching walk (we did it with an off-roading pram, its occupant and an additional toddler on a hot day, so it obviously isn’t that difficult) up the hill to a large complex of banks and ditches. The outer banks are now topped by beech trees and surround a village-size area of almost level ground, perfect for kite flying and exploration.

The view from the Ordnance Survey trig point is amazing and well worth the walk up the hill.

Lay-by of the week: The double-yellow years

We’ve used this location because it’s a great view of Burgh Island, the Art Deco hotel that everyone from Agatha Christie, through Churchill and the Beatles have stayed at and the magnificent sand spit that connects it to the island. Caused by the refraction of waves around the island, this particular spit is a classic example of a tombolo.

View Larger Map

In Shetland, tombolos are known by their Norse word, ayre. At the romantically named Ayre of Swinister, two tombolos enclose a coastal peat lagoon known as the Houb.

View Larger Map

Lay-by of the week: Chesil Beach from Portland

View Larger Map

You can get an even better view from the New Ground car park - follow the big arrow on the Street View below - but the Google car driver neglected to have their sandwiches in the lay-by that day.

View Larger Map

Lay-bys of the Week: Ravenscar and the Hole of Horcum

View Larger Map

Further inland, on the A169 between Whitby and Pickering, lies the stunning vista of the Hole of Horcum - a spectacular, 400 feet deep natural amphitheatre, three-quarters of a mile across formed by glacial ice.

The Hole of Horcum is the first place in Lay-by of the Week to be close to one of those top-secret, hush-hush places perfectly visible to anyone with some petrol money and a valid tax disc, but shrouded in the strangely impenetrable Googlemist for virtual passers-by. It's incredibly foggy for about 50 yards outside the Yorkshire "RAF" base and none of the usual Street View navigation controls work. Presumably, if you stick around for too long, some men in balaclavas will crash through your ceiling and confiscate you. Stick to looking at the Hole of Horcum, if I were you. Lay-by rating 4/5.

View Larger Map

Lay-by of the Week: Passing Place special

View Larger Map

Lay-by of the Week

View Larger Map

If you pan to the right, you'll see the lay-by itself. Further down the A498 there is a closer view of Llyn Gwynant on a sharp bend of the road and excellent views up the valley - an enchanting vista on a fresh spring morning.

View Larger Map

View up the Gwynant Valley.