Setting Your Boundaries

There are hundreds of miles of Bronze Age dykes in Britain, although not many of them are as impressive as the deep ditch and high rampart of Bokerley Dyke - a feature which has been shown to predate the Roman occupation. Not much is known of their use as prehistoric borders except that the smaller dykes are believed to be property, rather than territorial, boundaries. Bokerley Dyke’s survival since the Bronze Age is the outcome of its continual use for thousands of years; its upkeep, modification, reiteration and reinvention are all factors in its continued existence in the 21st century and you don’t have to look far to see what an achievement that is.

Looking south from the crown of the dyke, the landscape of East Dorset re-asserts the consensus view of post-war countryside; the familiar layout of arable and dairy, of copses that cling to the hillside and of lone trees apparently stranded at the centre of fields. Tramlines of tractor tracks skirt around each oak or ash like decorative ripples around an island map. In a large field, a solitary tree is often all that is left of a grubbed-up hedge, but here there is a line of them, cast adrift from the field’s edge on a long green island that joins together a pair of Neolithic long barrows.

The barrows are at the northern end of what may turn out to be an even older boundary than Bokerley Dyke. The Dorset Cursus is an enclosed linear earthwork up to 100 metres wide that runs for ten kilometres to the south west – by far the largest of at least 150 similar ancient monuments all over Britain. Nobody knows what purposes they served. Even the most popular theory, that they were processional walkways, doesn’t ring true because their design often included obstacles like boggy valleys and rivers and would make for the most ungraceful procession imaginable.

The location of a cursus often displays a preoccupation with the landscape itself, particularly rivers, but also on the transition from one kind of geology to another. There is some suggestion that they may also be figurative boundaries – perhaps an enclosed limbo between ‘wild’ and ‘domesticated’ land, or as at the Stonehenge cursus, between the landscape of the dead and that of the living. The Dorset Cursus crosses land between tributaries of the Hampshire Avon and those of the Stour, running roughly along the natural spring line.

As far as archeology has been able to tell, the Neolithic in Britain marked the dawn of a spirituality rooted in the relationship between the sky and the land, a practical theology that successfully linked astronomical events to agricultural practise. Our first artificial boundaries may have sought to mark out different kinds of land according to those beliefs, but by the Bronze Age, these sacred lines were dismissed in favour of more earthly divisions.

The Strange Day that a Five-Acre Hole Disappeared

In search of Angelina Sedgwicki: A five-acre hole on a Welsh hillside proved surprisingly elusive. ©Ian Vince

On a damp and squally warm Welsh day in late summer, I make my way up a steep track that runs along the edge of an ancient wood. I am in search of something exotic - the distorted fossil of an Angelina Sedgwicki, a half billion-year-old Trilobite a little under two inches in length. The fossil, according to a guide book I had recently uncovered in a secondhand bookshop, is apparently fairly easy to find - perhaps within a quarter of an hour or so of diligent rock splitting in an abandoned quarry on the other side of the hill - a statement I accept completely without question.

The trilobite I am looking for was laid down in mud and then squeezed as if in the jaws of a vice when two continents collided 430 million years ago. It was the same process that contorted muddy shales into the Welsh slate that still roof the Victorian suburbs of industrial English cities and I would apparently discover at least one contorted specimen splitting those slates apart. However, in order to do that, I have to find the quarry first and it seems to be peculiarly elusive for a five acre hole in a Welsh hillside.

Following the directions, I pass through a gate and struggle up a path that runs between ancient dry stone walls carpeted in moss. The wood is musty, its air thick and oppressive and every warm breath is filled with the cloying scent of chlorophyll before a summer storm. My asthmatic wheeze is accompanied up the hill by the nearby whistle and puff of a Welsh steam engine - recently re-purposed from carrying rock to ferrying tourists - which seems strangely apt, as I am the latter in search of the former.

The path levels out for a few yards as it crosses the saddle of the hill, then plunges down the other side towards the meadows of a flood plain. On this side of the hill, the geology of the area suddenly asserts itself on the path’s character. The wall incorporates thick slate within its structure and the footpath becomes strewn with large, loose slates making an unconsolidated scree upon which every footstep is uncertain. I elect to walk down through a stream bed that threads its way from one side of the path to the other, preferring the discomfort of wet feet to a long slide towards certain concussion. This trilobite, I tell myself, had better be worth it.

After ten minutes of alternate squelching, slipping and side-stepping my way to the foot of the hill, I find myself in the corner of a field, the expected location of a quarry which isn’t there. I check the map, read the directions and peer back up into a wild wood of tangled hornbeam and oak. I can just about make out what looks like a face of rock, but it may as well be on the other side of a barbed wire thicket - the wood is utterly impenetrable. A mosquito rasps into my ear, just one of hundreds buzzing around like paparazzi on mopeds circling their quarry, while I completely fail to get near mine. However, a few large boulders of slaty shale have tumbled onto the edge of the meadow and I spend twenty minutes with a hammer and chisel breaking rocks, all to no avail. I eventually give up, down tools and give in to a mind-altering mix of perspiration and disappointment.

I sit on a rock, take stock and try not to think about climbing back up the path. Sitting there in the quiet, I hear an almost metallic, ‘chip, chip’, which is quickly followed by ‘peek, peek’, a sound which has a chalk-squeak-on-a-blackboard quality about it - a grating, citric creak that seems more at home between your teeth than in your ear. Following the sound, my eye is drawn to a flash of short, white tail feathers and a streak of rusty brown. I find my binoculars and after a moment of searching along a branch of hornbeam, I locate the most exotic creature in the woodland, bar none - a Hawfinch. What gives it away, for the two seconds it is in plain view, is its bull-headed appearance and enormous gunmetal blue-grey beak - one field guide calls it a ‘flying pair of nut-crackers’.

The Hawfinch is characterized as being shy but, as it generally spends most of its time in the canopy of mature woodland, elusive would be a better description. After thirty years of looking out for one, this is my first and seeing it for the first time is a spectacular moment of triumph. It flies quickly back into the canopy and is soon lost again. After that, the trilobite is just history.

Layby of the Week: Ranmore Common

View Larger Map

By Eck, Layby of the Week returns

View Larger Map

Unravelling the mysteries of Stonehenge

Tyneham, Dorset

The scenery along the Jurassic Coast often informs even the casual viewer about how the landscape came to be the way it is; folded and contorted rock and the landforms it produces show off the brute force of nature well.

How odd, then, that some of this natural wonder has become the venue for more brute force, in the shape of enormous live firing ranges for the British Army. It's 70 years since the War Department took over the tiny village of Tyneham, in Dorset, to train for D-Day, with promises that it would be returned after the war. So far, those promises have turned out to be hollow while the Army’s early stewardship of the historic village was close to scandalous.

After concerted campaigns from the 1940s to 1970s, Tyneham - now wholly owned by the Government, was opened to the public on weekends and during the school holidays.

Having said all of that, when "trespassers will be shot" becomes the reality and there is no modern farming to contend with, wildlife has generally done well in this hidden valley, mirroring a similar situation on Salisbury Plain and in the Norfolk Brecks, both battle training areas.

I go into a lot more detail about the twisted history of Tyneham in November’s issue of Countryfile (on sale at the end of the month).

A Sense of Place

We tramped in total darkness across the Penwith moor in search of Chûn Quoit, the ancient remains of a round barrow – the final resting place of some long-forgotten tribal chieftain. To anyone who hasn’t seen one, a quoit – the Cornish name for a cromlech – is a structure that calls to mind the offspring of a colossal stone mushroom and a 12 foot milking stool. Four granite ‘legs’, each a slab of 20 tons, support a substantial capstone, all of which would once been hidden under a mound of earth. With its bare bones revealed there is an elemental quality about the structure – even on a bright day it has an austere menace that would put the willies up Boris Karloff, but picked out in torchlight against the midnight sky it was quite terrifying. The terror was all the more real because the night before, in a well-lit, warm and comfortable house, I had volunteered to sleep in it in the name of cognitive archaeology.

The idea was to record my dreams and to analyse them to see if they contained any interesting symbolism – symbolism which would hint at some hidden aspect of the place. My guide, companion and the man who would note down my nocturnal ravings was Paul Devereux, author of a slew of books on earth mysteries that treat the fluffy air-head dogmas of new age thinking with the skepticism they deserve in favour of original research into the unanswered questions raised at the fringes of science, culture and anthropology.

Paul happened to be a neighbour of mine and we shared a common interest, though my investigations of the fortean world were shambling and shallow in comparison. Only a couple of nights before he had handed me a sachet of what looked like sweepings from the barn floor to make up into a cold tea. The sawdust and twig infusion claimed that it would open up the third eye and help me to dream of interesting things but it tasted as bad as it looked and my third eye remained firmly shut, possibly in disgust.

We picked our way over the rocky terrain that lay between our car and the quoit, determined to keep to the well worn path. This part of Cornwall was mined for tin ore until the nineteenth century and some of the miners moonlighted on their own undocumented tunnels to make ends meet. As a consequence, Penwith has more holes in it than cartoon cheese – a fact that is underlined periodically when a cow goes hurtling down a mine shaft or somebody’s driveway unexpectedly disappears into the abyss.

After a quarter of an hour we arrived at Chûn and I crawled through the narrow opening.

To say the chamber was dank and claustrophobic doesn’t do it justice. Imagine a very small tent made out of five slabs of rock leaning on one another in a house of cards configuration, except that the cards weigh as much as 20 tons each. Rounded fragments of granite, rooted in the floor of the chamber, found hitherto undiscovered vertebrae which ever way I shifted myself to get comfortable, but it was the gnawing sense of ill-ease that was the real enemy of rest. Outside the chamber, the sky was as black as a bin liner, but inside, my mood had darkened to match.

Paul explained what the plan for the evening was. I was to doze off and be rudely awoken once I had begun to dream, at which point I would be expected to babble it all out before it had a chance to scuttle away into the night or my conscious mind made too much sense of it.

“But how will you know when I’m dreaming?”

“You’ll go into REM sleep – and I’ll be able to pick up your rapid eye movements with this”, said Paul, as he dug into his knapsack.

I half expected him to present me with a little scientific gizmo of some kind – maybe an electrode for my temple, a sensor on the end of a colour-coded wire or a coiled cable that led to an adapted moped helmet. So I was quite disappointed when he pulled out a bicycle lamp – a rear lamp which, he informed me, would enable him to catch my eye movements without disturbing me unduly.

It took another hour for my mood to melt from its agitated state. I was just drifting off peacefully, snatching the first images of the night, feeling the hypnogogic whirl into the vortex of dreams when I was pulled back from the brink of the plughole by the glow of a bicycle lamp in my eyes. After gabbling out some inconsequential mutterings, it was clear that we were all a little disappointed. We went home, exhausted, with no concrete dreams and only the memory of dark menace to console us.

From

Naenia Cornubia

A descriptive essay illustrative of the sepulchres and funereal customs of the early inhabitants of the County of Cornwall.William Copeland Borlase, BA, FSA

CHYWOONE CROMLECH

The most perfect and compact Cromlech in Cornwall is now to be described. It is situated on the high ground that extends in a northerly and westerly direction from the remarkable megalithic fortification of Chywoone or Chuun, in the parish of Morvah.The " Quoit" itself, which, seen from a distance, looks much like a mushroom, is distant just 260 paces from the gateway of the castle; and about the same distance on the other side of it, in the tenement of Keigwin, is a barrow containing a deep oblong Kist-Vaen, long since rifled, and now buried in furze.

Thinking this monument the most worthy of a careful investigation of all the Cromlechs in the neighbourhood, the author proceeded to explore it in the summer of 1871, with a view to determine, if possible, the method and means of erection in the case of such structures in general.

Layby of the Week: Knockan Crag

View Larger Map

Staying in Scotland – and not so far from last week’s layby on the A837 to Lochinver – another worthwhile stop-off on the west coast Rock Route designated by Scottish Natural Heritage, the Knockan Crag National Nature Reserve car park, near Elphin on the A835.

The Knockan Crag NNR is amazing. An unmanned visitor centre open all-hours, all-year with information and interactive displays on the landscape and geology of the area and two circular trails for different abilities, a car park and toilets. There are beautiful rock sculptures in the, frankly, prehistoric landscape and glorious views of Loch and Lochans stretching out at your feet. There are plenty of steps, but there's also a wheelchair/pushchair-friendly path to the Rock Room with its hands-on displays and touch-screen computer.

It's all in honour of tectonic forces that were strong enough to weld continents together, create the mountains and slide a huge block of ancient landscape dozens of kilometres over the top of younger rocks. All of that happened at Knockan Crag.

The Rock Room is a short, easy walk from the car park and it comes recommended.

Layby of the Week: Assynt

View Larger Map

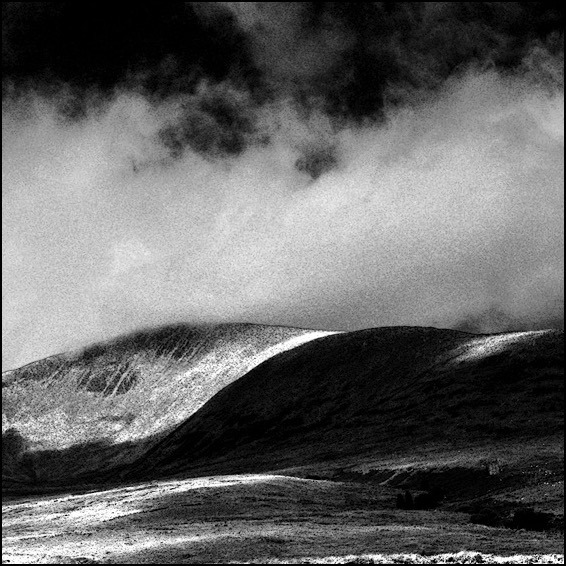

The Lewisian Gneiss here is between two and three billion years old and is all that survives in Britain of our Canadian connection, when this part of Scotland was also part of the ancient nucleus of North America. The policeman’s helmet mountain on the horizon is Suilven, about 4 miles to the south east of this layby and is made of comparatively young (only one billion-year-old) Torridonian sandstone.

Reading the Landscape Column

Reading the Landscape is a layperson’s guide to identifying the curious lumps and bumps, odd hummocks, ditches, landforms and buildings that can be found in the British countryside. It appears every month in the Month in the Country section of BBC Countryfile magazine and each instalment will appear here the month after. I may also add the odd extra thing I turn up in my travels around the British landscape.

Round Britain Quiz.

All of the following pictures are taken from roughly the same place. Where is it?

Here are some clues:

- The place is on an island a short distance from the UK mainland.

- The first picture includes the tip of an island (in the foreground) off the coast of this island, with the UK mainland in the background.

- The island in the first picture has a romantic connection, but not to St Valentine.

- The lump of rock in the second picture is a particular kind of lava

- An indigenous mammal lives in the woods.

A Meeting at Bokerley Junction

A silver birch stands alone at the centre of a square patch of rough ground. Its prominence would normally single it out as an excellent meeting point, were it not for the fact that it grows on a Second World War firing range in Hampshire, close to the spot where the county boundaries of Wiltshire, Hampshire and Dorset all meet on a National Nature Reserve. It might seem as though it’s verifiably bang slap in the middle of nowhere, but I’ve wandered around lonelier shopping centres and there’s a lot more going on here than meets the eye.

The birch is a thousand yards or so from Bokerley Junction, a knee joint bend on the A354 halfway between Salisbury and Blandford at Martin Down. Despite the implicit suggestion of more than one road, you’ll only find the A354 in your motoring atlas and actually driving along the A354 will get you no further, except that you might notice its pot-holed, oxbow lay-by left behind after improvements to the original road were made. But there is another road at Bokerley, the Roman Ackling Dyke which ran on 50 feet wide, 6 feet high overstated aggers to dominate the landscape between Badbury Rings, near modern Wimborne, and Salisbury’s forsaken precursor, Old Sarum.

The modern road and Ackling Dyke all come together to meet another nominal dyke at Bokerley – a defensive, linear earthwork, over three miles long and originally from the Bronze or Early Iron Age but then augmented in the 4th century by Romano British tribes to keep out the Saxons. The Romans showed their contempt for the local population by driving Ackling Dyke straight through Bokerley Dyke, then their descendants sealed off the road and beefed up Bokerley, a strategy which kept the Saxons out of Dorset for 200 years – a final martial use for a political boundary which still marks the border between Dorset and Hampshire.

Bokerley Dyke snaking its way southeast. The Saxons would have tried to invade from the left

Just to the south of this boundary lies the far northern end of the Dorset Cursus, a 5,300 year old earthwork over 6 miles in length, the exact purpose of which is something of a mystery. It starts (or ends) just to the right of this exceptionally long longbarrow (below), but most of its outline is only discernible from crop-marks as it has been ploughed out for the majority of its length.

Further south, Ackling Dyke parts company with the A354 again and strides out confidently across Bottlebush Down and beyond, taking extra care to defile the cursus on its way.

Lines on the Land

Living Memory

Four-and-a-half billion years in a minute

The war on tourism

Thank the stars, then, for Counter-Tourism and its network of related mytho-geographical sites. From the splendid examples of historical duplicity to tips and tactics to develop your own counter-touristic approach, the site invites you to transform your experience of the heritage industry. Recommended.

Britain’s Hidden Wonders in Countryfile

For further details check out the Countryfile Magazine website.

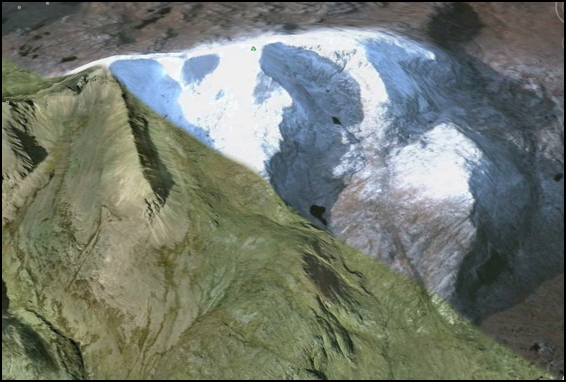

Northwest Highlands Google Earth fly-by

The complete tour takes about 17 minutes; if you are desk-bound for lunch, we’d recommend chomping your sandwiches as the Northwest Highlands float by underneath for a more relaxing break than might usually be the case.

We’ve kept it simple for now - no narration or music to accompany the scenery, but we might get bold in the future. We hope you enjoy the view.

Download Seventeen minutes in the Northwest Highlands.

Google MountainView 1

View Larger Map

This view, near the top of the winding lane that follows the Watendlath Beck from Derwent Water up to its eponymous Tarn, complete with lay-by encapsulates everything that is wonderful about the Lake District the glaciers left behind.

Applecross Cave discovered

The cave, near Applecross on the west coast, is 180 metres long and has stalactites measuring up to 2 metres. For Metropolitan types, that’s the length of ten bendy-buses, or Russell Square. More information at the link.

Layby of the Week: Llyn Cwm Bychan

View Larger Map

If your browser does not support Google Earth’s plug-in, you’re out of luck if you’re waiting for the Google Street car to arrive - this spot is simply too remote. Fortunately, the British Landscape Club have got there before you.

At the head of a remote valley and at the heart of the Snowdonia National Park, this Welsh lake sits at the centre of an eroded away dome - the Harlech Dome - of buckled rock that once bridged Snowdon in the north to Cader Idris in the south.

The lake is fed by the Afon Artro stream, the valley of which provides a mean transport corridor, enough for a hairy single track most of the way up from the village of Llanbedr on the coast road near Harlech. There’s a full account of its wonders in the Club manual, The Lie of the Land by Ian Vince, but all you need to know is that there’s a car park, a portaloo and moments of unfettered wilderness and blissful peace around this amazing spot.

Layby of the Week: Silbury Hill

View Larger Map

If your browser does not support Google Earth’s plug-in, here’s a real view of Silbury Hill, taken from just down the road by the Google Street Maps car.

View Larger Map

Either way, it’s an impressive structure - Europe’s largest man-made hill, it rivals some Egyptian pyramids in size and was built over successive generations from about 2400 BC. It is located in a landscape of dip and scarp, gently undulating chalk downs occasionally punctuated by imposing escarpments.

The recently synthesized view is that Silbury Hill, successive excavations of which have yielded no burials, was constantly tinkered with by our Neolithic ancestors as a kind of devotional labour, perhaps commemorating their ancestors who laboured for thousands of years building a ritual landscape in and around nearby Avebury, the site of the largest henge in the world - itself a devotional labour of epic proportions.

There’s a layby and viewing area a little to the west on the A4.

A view of a tiny part of the henge at Avebury.

View Larger Map

An aerial view.

Infra-red landscapes II

Lay-by of the Week - St David’s Day Special

View Larger Map

These two shots were taken from approximately the same position and look up and down the valley. The rocks around this part of Snowdonia are a complex mix of mud and sandstones with volcanic tuff (ash) and all manner of igneous intrusions formed from magma cooled slowly underground.

Famous landscapes:

Gold Hill, Shaftesbury, Dorset

The views look south towards a landscape made from Cretaceous chalk and greensand and older mudstones and siltstones from the Jurassic period. To the west of Shaftesbury the Jurassic continues - with many of the same limestones that are found in the Midlands cropping up, lending the area its Cotswolds atmosphere.

Infra-red Landscapes

Landscape blog

On our occasional trawls around the internet in search of snippets to amuse we often find hardcore walking and rambling sites - all kit and kaboodle and useful instructions for getting a platoon to the top of a mountain. All well and good but, apart from the picture from the summit, the journey always seems more like a technical challenge than an engagement with the landscape.

We were pleased, then, to find Alan Rayner’s Blog on the Landscape. Alan’s posts are illustrated with some thoughtfully composed photographs of this and that along the way - mostly natural features, plants and fungi - and his woodland shots, often difficult to capture well - are lovely.

Kit fetishists will be pleased to discover that Alan - an engineer by trade - appears to have designed and manufactured some of his own lightweight equipment and is always on the lookout for more, but a genuine love of the landscape permeates the blog. Recommended.

Lay-by of the week: Autumn Leaves

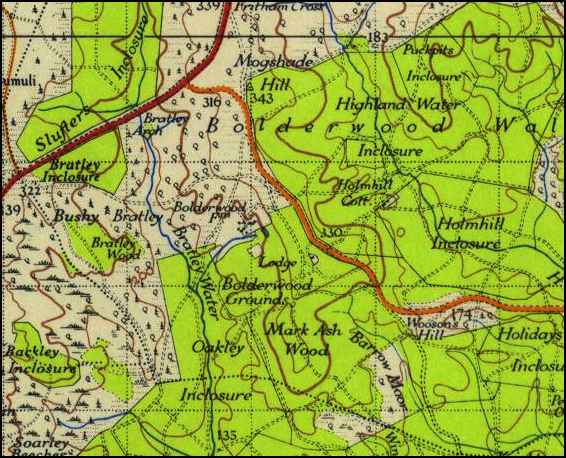

A special lay-by of the week this week from Bolderwood in the New Forest; not so much a lay-by as an interesting place to park, courtesy of the Forestry Commission.

View Larger Map

Ordnance Survey 1 Inch New Popular Edition 1945

During the summer months, the wildly interesting information kiosk (run-of-the-mill town centre TICs please take note) is open and on a busy weekend when the weather is nice you will often find an ice cream van parked up. But all of that is moot, because a short walk from the car park is a deer viewing platform - from where you may be lucky enough to spot a Red Stag or a group of Roe Bucks - like the picture below.

It’s also a timely reminder, as autumn passes into winter, of the importance of trees in the landscape, both from an aesthetic and functional view. Our forests are rich habitats that, like all woodland the world over, need to be managed and preserved not only for the good of some abstract ecological notion, but also because indiscriminate felling or management of them for anything other than their natural value is madness. The Coalition Government has recently announced it is to sell off up to half of our national forests. Not only would this put habitats and wildlife in severe danger, but it wouldn’t even raise very much money - making it all look less like a response to a financial crisis and more like an ideologically-sponsored privatisation; less like selling the family silver, more like putting our back garden up for sale. Anyone who cares about our landscape is strongly urged to join over 35,000 signatories (in the first week alone) and sign the 38 Degrees petition now - maybe they’ll think again when they see the numbers.

The Dabbler: The Lie of the Land

Lay-by of the week:

The Cow and Calf Rocks, Ilkley Moor

Overnight, a thick fog descended, but 35 people dutifully turned up to follow me around the Cow and Calf anyway, despite visibility beyond the end of one’s arms becoming difficult, so this week’s lay-by of the week is dedicated to the helpful folk of Ilkley and its environs.

View Larger Map

NB, For aesthetic reasons, the Googlecar is a little below the Cow and Calf car park in this shot.

Landscape appreciation

Lay-by of the week:

Porlock Bay and Selworthy

View Larger Map

If you’re driving on the A39, the road that connects the main towns of North Somerset and Devon, chances are you’re not getting anywhere very fast, so why not relax and make a detour to the village of Selworthy. This is the church car park in the village - rotate the panorama a little for a view of Selworthy’s beautiful white church.

View Larger Map

Lay-by of the week:

Loch Ness and the Great Glen

View Larger Map

The fault is a tear fault - the landscape to the north moved around 80 miles south-west then, in a second phase millions of years later, 18 miles back in the opposite direction. Loch Ness - which is, on average, around 600 feet deep owes its formation to the fault: glaciers carved out the trench from the band of shattered and pulverised rock left by it.

There is also strong evidence which links it to the Cabot Fault, which runs the length of the north west coast of Newfoundland and into the Gulf of St Lawrence. When the faults were formed, over 400 million years ago and long before the Atlantic Ocean formed, Scotland was part of the same landmass as Canada.

View Larger Map

Lay-by of the week: Symonds Yat

Again, it’s not, strictly speaking, a lay-by - more of a car park that leads to a view - but it’s only a very short walk and thousands come every year to see the view up and down the River Wye. It’s home also to Peregrine Falcons, Buzzards and Goshawks and is well worth the detour. It also makes an excellent place to watch the stars at night, according to some.

No Google Street View this time, but an OpenStreetMap image.

View Larger Map

Lay-by of the week: Cheddar Gorge

View Larger Map

The gorge was carved out in periglacial conditions during the recent glaciations of the current Ice Age. Though too far south to have had glaciers, water in the limestone from which the gorge walls are made, froze and rendered the normally permeable rock impermeable. Meltwater floods in the summer months flowed over the limestone and cut a deep channel which is the gorge we see today.

Dartington

More pictures from trains

I’ve added a few more photos to the gallery of landscapes taken from trains. It seems like an unconventional way of capturing scraps of scenery as they zoom by and an excellent mental diversion when the novelty of getting out and about wears thin which, as any commuter on Britain’s railways will tell you, can be quite quick.

If you have some train pictures you want to share, feel free to add some in the comments below.

Lay-by of the week:

The Glen Café, St Mary's Loch

View Larger Map

The lay-by, meanwhile has just about anything you could desire, including a café, phone box, tourist information panel and fantastic views over St Mary’s Loch and it’s southern neighbour, the Loch of the Lowes. Looks like a charming spot. We’d give it a 4.5/5 Thermos rating, but there’s no need to bring one.

Lay-by of the week special:

The views from a Devon train

The trains I travelled on were the Great Western 125 mph from Totnes to Exeter and the more modern but 90 mph from Exeter to Salisbury. On my way to Exeter, I was hoping to catch a good view of the fantastic New Red Sandstone cliffs around Dawlish, as featured in The Lie of the Land. I got something of it, through the fly carcasses, and it looks like an old double-exposed holiday slide that has been wedged under a shelf in the garage since the 1970s. It was, at least, nice to make something that came with an instant patina of age on a digital camera.

The second two shots are nearer Exeter, of clumps of trees on the Exminster Marshes. By the time that I had got on a cleaner train, I took some more presentable shots of the kind of thing you see from trains, this time mostly between Exeter and Yeovil. This first shot is of some trees in the Axe Valley - I’m hopeless at trees, but they’re in the right environment for Alder and Willow. I like the way they’re all leaning here, as if in agreement with one another.

The second shot is quite near Yeovil. The reflections from the train’s internal lighting give the sky some go-faster stripes.

Lay-by of the week special

ROAM: The London Lay-by Library

ROAM at Hollow Ponds, Whipps Cross Road

ROAM is touring the five Olympic boroughs of London over the next three weeks as a peripatetic arts space, a mobile reading room and a venue for talks and performance. It has its own reference library and comes complete with a proper parquet floor. It’s the idea of Caught By The River’s Robin Turner and fits well with that website’s general ethos of taking solace in easy, idle pursuits and looking for the rural within our urban lives.

I’ve already had the pleasure of taking the message of the British Landscape Club there and chatting about the Britain beneath its wheels and I’ll be doing it again three more times over the next week and a half, so come and join me.

Friday 9 July 3pm *NOTE NEW TIME*

Beneath Our Feet: Three Billion Years an Hour Through Britain’s Past

ROAM London: Haggerston Park • Parked up behind the tennis courts • E2 8NP

Friday 16 July 7.00pm

Beneath Our Feet: Three Billion Years an Hour Through Britain’s Past

ROAM London: Mile End Park • Grove Road • E3

*NOTE NEW VENUE* (Was at Truman Brewery)

Monday 19 July 7.30pm

Beneath Our Feet: Three Billion Years an Hour Through Britain’s Past

ROAM London: Oxleas Woods • Shooters Hill • SE18 3JA

Lay-bys of the week:

Cape Cornwall and Lizard Point

The text book definition of a cape, by the way, is a promontory where two major bodies of water meet - in this case the Atlantic and St George's Channel. Since those nineteenth century OS men declared Lands End as further out in the ocean it is arguably where the waters meet rather than Cape Cornwall, but the name stuck anyway.

View Larger Map

Meanwhile, there’s no such controversy about Lizard Point, mainland Britain’s most southerly spot. There’s a National Trust car park there as well and a bonus collection of sheds that sell souvenirs carved from the local rock. This rock, serpentine, is metamorphic in origin, 400 million years or so old, and an excellent example of a bit of oceanic crust that has unaccountably slid over the top of a piece of continent (it almost always slides under when the two collide).

You might like a cup of tea, while you contemplate that and, besides one of the souvenir sheds, lies the cafe with the best view in all of Cornwall (below). It’s always busy in the season and it’s always worth the wait. You may even be fortunate enough to see a couple of Cornish Choughs wheeling in the sky, failing that you can stare at the cliff that rings with the sound of Jackdaws and Kittiwake and hope to catch a glimpse of a Peregrine or two.

View Larger Map

Monstrous Carbuncle

But one of those towns – and not just any old market town, but Dorset’s county town – will never be the same again. For Dorchester has been tainted by its association with the monstrous carbuncle that is HRH Prince Charles’ Poundbury or, to give it a name accidentally arrived at in a Freudian slip of the tongue, Poundland.

View Monstrous Carbuncle in a larger map

This grotesque and repulsive display of architectural pus sits on the eastern horizon as you approach Dorchester from the west. The awful buildings infect the surrounding landscape with their weak-minded parody of a passing resemblance to a rough similarity to a half-remembered Tuscan hill-top village. Who-ever presided over this inferior and wholly unaesthetic effort should be shot through the lungs with high-velocity 2H pencils.

Some of Poundbury is well-executed, even if it is obviously the work of a cobwebbed mind. While the Duke of Cornwall proclaims his love of traditional vernacular architecture and actually has interesting and useful ideas about the sustainability of communities, his biggest showcase looks like a malformed bleb from the side of the A35.

Lay-by of the week: Askerswell from the A35

View Larger Map

One bright and crisp winters day a short breath after Christmas, we were driving through Dorset as we made our way back from Cornwall. The journey was quite familiar to me and I had never given it much thought. A couple of years before, I had come the closest to thinking deeply about travel when two friends and I covered the same ground as part of an epic, 15 mph journey across England in an electric milk float but, crucially we had picked a different route for this stretch.

I was on the A35, a murderously busy road we had escaped from while on the float - a quick turn-off that happened to land us in Arcadia, an enchanted valley near Little Bredy trapped somewhere between dusk and the early 1950s. It was the encapsulation of pastoral beauty and I will remember the scene for ever.

As so often happens in Britain though, by catching one thing, you miss another and the A35 - for all its homicidal ways - is the scene of something on a par with our Dorset Arcadia but in a different way. The stretch of it we avoided, between Dorchester and Bridport, affords awe-inspiring views of the lumpy, bumpy Dorsetshire hills, the festival of buxom hummocks that made it into the introduction to The Lie of the Land.

As ever, all attempts to capture such grandeur on a soul-less semiconductor fail miserably. I’ve taken my version of the Google Street View, but the best stuff is on the other side of the road when the road reaches its height and the views over the Dorset coast are breathtaking. You really have to see the view for yourself.

Lay-by of the week: Danebury hillfort

View Larger Map

Danebury is a magnificent Iron Age hillfort a few miles north of Stockbridge. There are two car-parks, the lower of which is clearly visible from the Google Street View car, but visitors can make their way further up the drive to a second parking area partially under the cover of trees. It’s then a short, moderately stretching walk (we did it with an off-roading pram, its occupant and an additional toddler on a hot day, so it obviously isn’t that difficult) up the hill to a large complex of banks and ditches. The outer banks are now topped by beech trees and surround a village-size area of almost level ground, perfect for kite flying and exploration.

The view from the Ordnance Survey trig point is amazing and well worth the walk up the hill.

Lay-by of the week: Ynys Môn special

View Larger Map

Steve writes, "Between Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch and Menai Bridge there are two lay-bys. One is bigger and better than the other in my opinion. It sports views of many of the mountains of north wales (Carneddau, Glyders, Snowdon range [though not Snowdon itself I believe]), also the Menai Strait where you can see kayakers and little boats and the bridge built by Telford that gives the town Menai Bridge it's English name (it's called Borth in Welsh)."

Lay-bys of the week: Top & tail of Scotland

View Larger Map

The first is right at the top, on the north coast of Scotland at Heilam above the shores of Loch Eriboll, gazing from the top of one of the most violent upheavals in these islands’ prehistory - when huge blocks of crust were uplifted and pushed dozens of miles from the east. The peaceful view is that of the ‘foreland’ - the block that escaped all the pandemonium.

Far to the south on the Mull of Galloway - Scotland’s most southerly point - a road down the long peninsula leads to a car park with panoramic views of land and sea.

View Larger Map

British Volcanoes: Arthur's Seat, Edinburgh

Last time we looked at the remains of the caldera on the Ardnamurchan peninsula, a volcano that may have been the result of the same hotspot as Eyjafjallajökull but is, in any case, related by virtue of its eruption at the start of the rifting process which first opened up the Atlantic.

This time we are concentrating on a more urban setting, on a volcano that last erupted in the Carboniferous period (between 360 and 290 million years ago) in the middle of what is now Edinburgh. It would have looked very different then, when much of Britain was a tropical swamp and a kind of prototype dragonfly flitted around the marsh with a two-and-a-half foot wing span; when arthropods which bear a resemblance to modern millipedes reached lengths of over eight-and-a-half feet; when all of this gigantism was made possible by an atmospheric oxygen concentration not far from double modern levels.

The view from the slopes of Arthur’s Seat

Around other parts of what is now the Midland Valley of Scotland, coal was being produced in the swamps of a coastal plain that was not unlike the northern shores of the Gulf of Mexico today (without the devastating oil-spill, of course). For 50 million years, this tranquil scene was occasionally interrupted by volcanic eruptions. First at what is now the Castle, then later in Holyrood Park, eventually forming the feature now known as Arthur’s Seat.

In the related volcanic activity that formed Salisbury Crags (below), however, the molten rock never actually made it to the surface as a volcanic eruption, cooling deep within the earth instead. By the way, if you live in London and don’t have a snowball’s chance in hell of getting to see Salisbury Crags or are simply too metropolitan to countenance travelling beyond the M25, the mountain has come to you instead. A lot of London is paved with it.

Salisbury Crags

Salisbury CragsLay-by of the week: The double-yellow years

We’ve used this location because it’s a great view of Burgh Island, the Art Deco hotel that everyone from Agatha Christie, through Churchill and the Beatles have stayed at and the magnificent sand spit that connects it to the island. Caused by the refraction of waves around the island, this particular spit is a classic example of a tombolo.

View Larger Map

In Shetland, tombolos are known by their Norse word, ayre. At the romantically named Ayre of Swinister, two tombolos enclose a coastal peat lagoon known as the Houb.

View Larger Map

Lay-by of the week: Kylesku, Highlands

The view is of Loch Glendhu stretching off into the distance while Loch Glencoul forks, unseen, behind the nearest headland to the right. The die-straight diagonal line on the mountain behind the lamp-post is the fault plane of the Glencoul Thrust, one of a number of landscape movements caused by the joining of Scotland - originally part of the same landmass as North America - to the rest of Britain over 400 million years ago. Land was folded, fractured then heaved dozens of miles from the west, from the north at Durness all the way down the west coast to the Isle of Skye.

View Larger Map

Although the ferry no longer carries traffic across the Loch to Kylestrome, there are still boat trips from Kylesku - most notably up Loch Glencoul, from where you can enjoy superb views of Eas a’ Chùall Aluinn, at 658 feet, Britain’s highest waterfall.

Lay-by of the week: Chesil Beach from Portland

View Larger Map

You can get an even better view from the New Ground car park - follow the big arrow on the Street View below - but the Google car driver neglected to have their sandwiches in the lay-by that day.

View Larger Map

Win a hamper in our landscape photo competition.

To celebrate the launch of Lie of the Land, The British Landscape Club’s under-the-field-guide to the British landscape, we are running a photography competition to find Britain's best photographed landscape.

So get snapping those buxom hummocks, discordant coastlines and stone circles and submit them to the Lie of the Land Flickr photo pool at http://www.flickr.com/groups/lieoftheland/.

The winner - who will win a lovely picnic hamper - will be announced July 30 2010 Leading up to the announcement we will feature ten photos a week right here on the website. There will be also be runner-up prizes of signed copies of Lie of the Land.

For general competition terms and conditions go to:

http://www.panmacmillan.com/displayPage.asp?PageID=3823

Please be assured that your photos will only be used in connection with this competition and any publicity it generates - which may include the websites of national and local newspapers. The submitter retains all copyright to their photos and the right to a byline/credit where ever it is used.

British Volcanoes: Ardnamurchan

At the risk of sounding like a Travelodge brochure, Britain’s volcanic heritage can be discovered in many locations across the UK from the wilds of Ardnamurchan to the slopes of Snowdonia - there are even city centre volcanoes for your convenience. We’ll be looking at all of these over the next few weeks, but we’re starting at mainland Britain’s most westerly point - not Land’s End as is popularly supposed, but the Point of Ardnamurchan in Scotland.

View Larger Map

The Ardnamurchan Peninsula, seen here courtesy of Google, was the site, around 65 million years ago, of intense volcanic activity. Over a period of approximately three million years, the Ardnamurchan volcano would have undergone a series of awe-inspiring eruptions culminating in the collapse of the cone and crater onto the chamber of molten rock beneath, forming the caldera - the remains of which we see today. The hotspot that created it may even be the same plume that now lies under Iceland obstructing your travel plans.

In the intervening period, wind, rain and, the most destructive of them all, glacial ice, have worn down the landscape. The following image is from the southern part of the crater itself, while the view north - like most of the journey along this road - is obstructed by the lie of the land.

View Larger Map

Lay-by of the Week: Llyn Ogwyn

View Larger Map

Steve writes, “There are several lay-bys on this stretch of the A5 which are very popular with outdoorsy people. Looking west you can see Y Garn which has a nice cwm. and SSE you can see Tryfan, probably one of the best mountains in Wales. You can also see Llyn Ogwen, the lake alongside the road. You might prefer the lay-by closer to Ogwen Cottage as you can get a cup of tea there.”

Feel free to re-tweet the permalink and, as ever, if you have a favourite stopping-off point to view the scenery over a cup of warm thermos tea, drop us a line or leave a note in the forum.

Lay-bys of the Week: Ravenscar and the Hole of Horcum

View Larger Map

Further inland, on the A169 between Whitby and Pickering, lies the stunning vista of the Hole of Horcum - a spectacular, 400 feet deep natural amphitheatre, three-quarters of a mile across formed by glacial ice.

The Hole of Horcum is the first place in Lay-by of the Week to be close to one of those top-secret, hush-hush places perfectly visible to anyone with some petrol money and a valid tax disc, but shrouded in the strangely impenetrable Googlemist for virtual passers-by. It's incredibly foggy for about 50 yards outside the Yorkshire "RAF" base and none of the usual Street View navigation controls work. Presumably, if you stick around for too long, some men in balaclavas will crash through your ceiling and confiscate you. Stick to looking at the Hole of Horcum, if I were you. Lay-by rating 4/5.

View Larger Map

Lay-by of the Week: Passing Place special

View Larger Map

Lay-by of the Week: Laxford Bridge

So, another week, another lay-by, but this isn't any normal picturesque view but one which labours under the name of the Multi-Coloured Rock Stop. Some might find the joviality annoying but arguments about the presentation of science aside, the Multi-Coloured Rock Stop is an astounding feature. Three different ages of rock can be distinguished on the cutting opposite this layby and even the artefacts left behind by the road contractor's rock drills, the regular parallel incisions down the rock face, only add to the effect.

View Larger Map

The oldest rock here - the pale grey one - is one of the ancient Lewisian Gneisses of the North West Highlands, a rock that was brewed at high temperatures and under great pressure miles underground billions of years ago. Swirling across it with the twisted teardrop freedom of a Paisley pattern, is a dark brown-black basalt which, as molten rock, squeezed through a weakness in the gneiss. Finally, streaks of pink granite cut through both the gneiss and the basalt dyke and so must be the youngest of all three.

Human landscapes

Meanwhile, an article from last Monday's Times takes us to Maiden Hill in Dorset, the remains of a huge Iron Age hillfort a mile or two to the south west of Dorchester, to report that the coldest winter in 30 years has left the landscape 'burnt brown by frost'. Which is all true: pity though that the picture desk bought a slide of somewhere completely different to illustrate the article. 'Children enjoy the snow in Maiden Castle, Dorset, last month' runs the caption, under a picture of Gold Hill in Shaftesbury, perhaps more famously known as the location of the Hovis ad but, as completely missed by the Times' editorial team, 30 miles to the north of Maiden Castle.

Lay-by of the Week

View Larger Map

If you pan to the right, you'll see the lay-by itself. Further down the A498 there is a closer view of Llyn Gwynant on a sharp bend of the road and excellent views up the valley - an enchanting vista on a fresh spring morning.

View Larger Map

View up the Gwynant Valley.

Google Stone View

View Larger Map

Armchair travellers will be delighted to hear that there will be more coming up from Google Street View in due course. You can see a lot of interesting landscapes all over the UK and, although you should tramp out across them rather than admire them from afar, some of the locations make ideal spots to stop on long journeys.

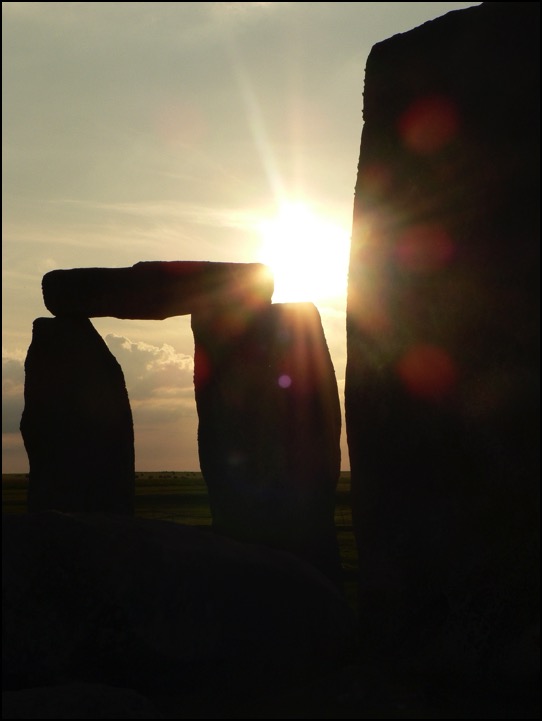

Stonehenge Landscape

The writer pays a visit to the Stonehenge Cursus and The Avenue and concludes that the surrounding landscape was manipulated by the builders of the henge to evoke a sense of wonder.

Here is a link to the online version of the article.