Independence or No, Scotland's Singular Past is at the Root of its Unique Appeal

Friday, 19 September, 2014. Filed under: Scotland

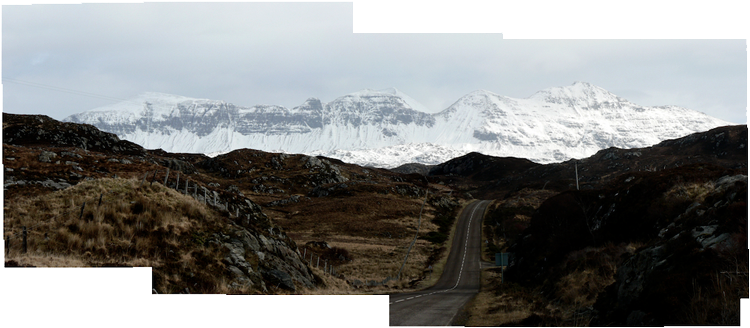

The Road to Lochinver in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland © Ian Vince

The Independence Referendum has ended in a ‘No’ Vote – albeit with a significant minority in favour – but the roots of Scottish independence run deeper than any year-long campaign or generational shift; Scotland’s distinctiveness is built into the very fabric of the country.

While the arguments about independence have always been less about getting rid of the English and more about a detachment from the ‘Westminster Village’ and bringing power closer to home, west of the road that connects Inchnadamph, Stronchrubie and Knockan Crag, a different form of power begins to become apparent. Here lies the basement rock of Britain – a slab of crust two thirds the age of the planet on which the entire edifice of Scotland is presumed to rest.

It’s a distinctive landscape that hints at an ancient independence; before the land that now forms Britain was welded together hundreds of millions of years ago, what lies below Scotland was actually a part of the Canadian Shield – formed deep within the Earth around three billion years ago, these rocks – the Lewisian Gneisses – are exposed here on open rolling moorlands, punctuated by countless lochs, lochans and Scottish puddles with mountains like the sugar-loaf inselberg of Suilven towering above.

The oldest rocks of England, by comparison, are relatively fresh at around 600 million years. What is particularly interesting is that these two landmasses are welded together miles underground along a feature known as the Iapetus Suture which runs roughly along the same track as the 300 year-old Scottish-English border. Iapetus was the father of Atlas, who gave his name to the Atlantic Ocean – the suture is all that is left of the Iapetus Ocean which once divided the proto-American continent of Laurentia with its pre-European counterpart, Avalonia. When the Atlantic opened up, bits of Laurentia were left behind in Scotland and parts of Avalonia ended up across the pond – chiefly parts of Newfoundland and, believe it or not, New England.

We have more in common with far-flung parts of the world than we may know, but places and people close to home can feel distinctly different for good reasons. These are lessons that Westminster seems set to learn.

blog comments powered by Disqus