Oct 2013

Trig Points

October 2013 Filed in: Human Landscapes | Buildings and Architecture

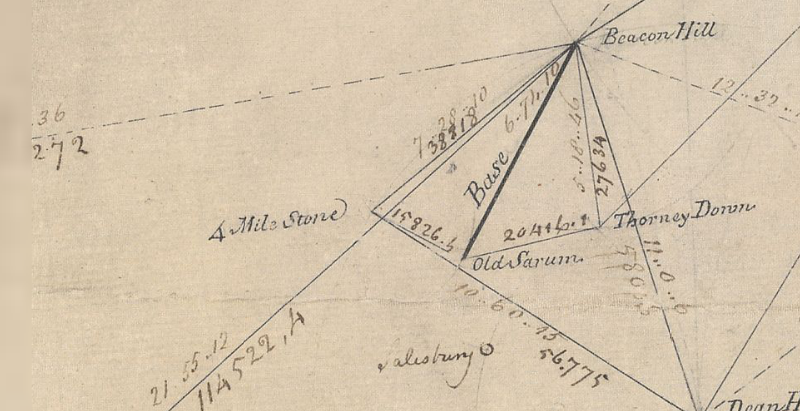

Just northeast of Old Sarum, the abandoned city that looms over younger, yet medieval, Salisbury, lies a monument important enough to be marked on Ordnance Survey maps, along with an intriguing inscription: ‘Gun End of Base’.

In many ways, it’s the most important point on the map, because if it wasn’t for Gun End of Base – actually the muzzle of a cannon buried vertically, business end up – there might not be a map at all. This is the spot where the first definitive mapping survey of Britain began in 1794, where initial measurements for the ‘principal triangulation of Britain’ were taken by Artillery man Captain William Mudge.

You can still see the snout of the cannon at Old Sarum, but the gun at Beacon Hill, 7 miles to the north where Mudge set his theodolite, was eventually replaced by a triangulation pillar, or trig point, 140 years later.

A small, tapered obelisk 4 feet tall and 2 feet square at the base, often found at the summit of a hill, the trig point is a welcome sight for walkers and climbers, although you don’t always need to scramble to the top of a draughty peak to bump into one; starting with Cold Ashby in Northamptonshire – in the middle of a rather flat field at SP644765 – there were around 6,500 built between 1936 and 1960, including one on the Little Ouse in Norfolk TL617897, a metre below sea level. Today, around 5,500 pillars remain at large, though only 110 remain in active service as part of a GPS-style network.

A familiar fixture in the British countryside since the OS built them to survey the country anew, the stability of trig points enabled surveyors to take very accurate measurements which allowed them to perform calculations that, in the trig point’s day, were accurate to 20 metres from one end of Britain to the other. Satellite technology has now improved that to just 3mm.

Trig points aren’t the only mapping artefacts you can discover in the field. Small metal plates marked with a broad arrow pointing up to a horizontal line, or ‘bench mark’, indicate a known height above sea level – and can be found on most pillars as well as the sides of churches, bridges and public buildings. They are joined by around half a million chiselled-out marks on walls all over Britain, which helped to define every last contour and spot height that appear on the map, often next to the triangular symbol that marks the trig point. And, as you catch your breath from the climb up to that pillar, you’ll see that if there’s one thing you can be sure of, it’s a fine view – of the next one.

Comments