Lumps and Bumps

Holloways and Green Lanes

November 2013

Of all the various roads and paths that snake their way through the countryside – A roads, B roads, byways and bridleways – it’s interesting to note that some ways are invested with a little more romance than the rest and by some ways, I mean green lanes and holloways.

While ‘green lane’ is a catch-all for many different kinds of unsurfaced rural road or path – such as an old drove, a coffin road or a ridgeway – a holloway is a more specific term. It describes a sunken green lane, a track which was been worn down by the passage of thousands of feet, cartwheels and hooves over hundreds of years, even millennia. With the loosened soil subsequently washed away by the next downpour, the course of a holloway will often become more pronounced on the side of a hill because of the extra energy imparted by the surface water run-off.

Holloways are common in lowland Britain with the greensands of the southern counties – Wiltshire, the Weald and the Chilterns – being particularly suited for their formation, as is the old red sandstone of the Wye and Usk valleys of Wales and the Marches, while the new red sandstone of south and east Devon has splendid, deep lanes on its slopes.

Over time, as they are inscribed ever more deeply and the level of the lane lowers, they become more sheltered and trees arch over, creating a womb-like tunnel, an enclosed place of natural safety. So safe, indeed, that it’s only around this time of the year that the walls of foliage have died back enough to get into some old lanes, long-since-abandoned by changing patterns of passage over the land, bypassed in favour of a better route.

Where holloways have fallen into disuse for even longer periods, they can be discovered anew – many centuries after they were last followed – by tell-tale shallow linear grooves through fields or woodland, though check that it’s not a short stretch of long-forgotten park pale or a defensive ditch, both of which will be accompanied by a bank above the natural ground level.

Holloways have their own atmosphere, an unexpected quality which cannot be explained away purely in terms of the local topography or geology. As ancient routes, they are the perfect expressions of collective will, tracks which share a common origin with desire lines – those unpaved paths across city parks or shortcuts over open ground that urban planners never anticipated. As travelling long distances was more difficult in the past, the reasons were more keenly felt; every footstep has meaning on a pilgrimage and the burdens shouldered on a well-used coffin road were more than the purely physical.

Comments

Deserted Medieval Villages

September 2013

The eternal peril of its pubs and post offices aside, it’s hard not to view the British village as something of an indestructible institution, but it wasn’t always such a permanent fixture and the threats that it faces now pale into insignificance next to the menaces of the middle ages, when entire communities could be smeared from the map on the say-so of just one person.

The ‘Medieval Village’ label on Ordnance Survey maps carries an inevitable presumption of plague, but the spectre of a multitude of whole settlements exterminated by the Black Death is an exaggeration. Conspicuously large churches, like the magnificent St Mary’s at Tunstead in Norfolk where construction work was halted by the Great Mortality (as it was known at the time) are perhaps better indicators of the plague’s effect; villages were certainly weakened and reduced, but they were not always completely extinguished.

The real menace of the middle ages – the agent of chaos that threatened communities up and down the land – turns out to be nothing more than the humble sheep. Innocuous and dim as individuals, in farmed flocks their role as woolly bailiffs was well-established before, and for centuries after, the Black Death left its mark.

Cistercian monks were among the first to farm sheep on the enclosed lands of evicted villages. The Cistercian craving for isolation found expression in the destruction of villages like Cayton and Herleshow in Yorkshire in the twelfth century, both given to Fountains Abbey in return for eternal salvation for their noble freeholders, while tenants suffered the temporal damnation of being forced to move on.

The Black Death would play its own merry part later. With a reduced working population demanding better terms, the manorial lords, perhaps inspired by the Cistercians, filled their lands with sheep. Wharram Percy in the Yorkshire Wolds, the most famous of Britain’s 3,000 abandoned villages, was finally cleared in the early sixteenth century and enclosure continued in England for another three hundred years. From the seventeenth century on, enclosure was increasingly for country house emparkment, where designers like Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown grazed on the profits of landscape enclosure in place of the sheep.

In Scotland, the ovine menace reared its ugly head once more in the infamous Highland Clearances of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Some of the most brutal of the clearances occurred at Boreraig and Suisnish on the north shore of Loch Eishort on Skye; families were forcibly evicted and sent packing, their homes burnt down. Geologist Archibald Geikie who happened to witness the eviction in 1853 described the cortege that led north along the track from Suisnish and the grief-laden wail echoing along the strath as a ‘prolonged note of desolation’.

The ‘Medieval Village’ label on Ordnance Survey maps carries an inevitable presumption of plague, but the spectre of a multitude of whole settlements exterminated by the Black Death is an exaggeration. Conspicuously large churches, like the magnificent St Mary’s at Tunstead in Norfolk where construction work was halted by the Great Mortality (as it was known at the time) are perhaps better indicators of the plague’s effect; villages were certainly weakened and reduced, but they were not always completely extinguished.

The real menace of the middle ages – the agent of chaos that threatened communities up and down the land – turns out to be nothing more than the humble sheep. Innocuous and dim as individuals, in farmed flocks their role as woolly bailiffs was well-established before, and for centuries after, the Black Death left its mark.

Cistercian monks were among the first to farm sheep on the enclosed lands of evicted villages. The Cistercian craving for isolation found expression in the destruction of villages like Cayton and Herleshow in Yorkshire in the twelfth century, both given to Fountains Abbey in return for eternal salvation for their noble freeholders, while tenants suffered the temporal damnation of being forced to move on.

The Black Death would play its own merry part later. With a reduced working population demanding better terms, the manorial lords, perhaps inspired by the Cistercians, filled their lands with sheep. Wharram Percy in the Yorkshire Wolds, the most famous of Britain’s 3,000 abandoned villages, was finally cleared in the early sixteenth century and enclosure continued in England for another three hundred years. From the seventeenth century on, enclosure was increasingly for country house emparkment, where designers like Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown grazed on the profits of landscape enclosure in place of the sheep.

In Scotland, the ovine menace reared its ugly head once more in the infamous Highland Clearances of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Some of the most brutal of the clearances occurred at Boreraig and Suisnish on the north shore of Loch Eishort on Skye; families were forcibly evicted and sent packing, their homes burnt down. Geologist Archibald Geikie who happened to witness the eviction in 1853 described the cortege that led north along the track from Suisnish and the grief-laden wail echoing along the strath as a ‘prolonged note of desolation’.

A Lot of Roman Around

July 2013

Known as Quintilis before Julius Caesar modestly renamed it in his own honour, the month of July is a fitting time to consider one of the most striking features of the British historic landscape, the Roman road. Although there are about 2,000 miles of them shown on Ordnance Survey maps, estimates of the total length of the network, including presumed minor thoroughfares undiscovered and skulking under fields, suburbs and industrial estates across Britain could expand it to around 6,000 miles.

They were built as logistical tools of empire, to move legions and supplies at speed and, it seems in some cases, to scare the willies out of the locals; Ackling Dyke on the chalk upland between Martin Down and Blandford Forum strides out across the landscape on an overstated, six feet high embankment that shows utter contempt for the barrows, dykes and cursus it merrily ploughs through. The bank – or agger – of the road, though exaggerated, is of a typical layered construction; indeed, the latin word for layers, strata, gave us the word street, an Anglo-Saxon place name often found along the course of Roman roads. Stretford, Stratford, Stretton, Street and their ilk are common names of settlements found along the way, while the Norse word for road, ‘gate’ – particularly when used with ‘stone’ or its derivatives Stan, Stane or Stoney – might also indicate the course of a Roman road.

In Europe the maxim holds that ‘all roads lead to Rome’ while in Britain, they tend to radiate from London. The Fosse Way – between Exeter and Lincoln – goes against the grain, however, and may have even started as a defensive structure during the early years of the invasion, then adapted later as a road and an enduring one, to boot; much of it survives as a taut thread of primary and secondary routes through a tangle of English country lanes. Despite their reputation for straightness (between Ilchester and Lincoln, a distance of 180 miles, the Fosse Way never deviates more than 6 miles from the crow’s flight) pragmatism forced Roman architects to make more concessions to the landscape over time and the Roman road eventually learnt how to bend.

Stanegate, which crosses the Pennines south of Hadrian’s Wall between Corbridge on the Tyne and the Solway Firth, is one such winding road. It connects at Corbridge with Dere Street, the most easily traceable Roman route into Scotland, running all the way to the Forth Estuary. Given that there’s evidence of Roman activity as far north as a line from Stirling to near Stonehaven and claims of a fort at Inverness, there are likely to be many more roads found, long-forgotten, on the outskirts of towns or hidden in the remote straths and glens of Caledonia.

Name that Tumulus

June 2013

Above: A bowl barrow on the ridge on Matley Heath, near Ashurst in the New Forest, Hampshire. Image: © Jim Champion | CC BY SA 2.0

With up to 20,000 burial mounds in Britain and ‘tumulus’ a common word on Ordnance Survey maps, it’s not surprising that wherever you go, a barrow, howe, hump, or tump is never far away; of all the ripples and bumps on the land, barrows are the most abundant hummock of all.

They might be ubiquitous, but they’re far from uniform, occurring in a wide variety of shapes influenced by geology, the materials that were available and the shifting cultural trends of 4500 years. In some places, these different species of barrows occur as swarms around other features – especially henges (there are around 300 barrows in the immediate vicinity of Stonehenge alone) while others appear to have a relationship to parish borders – vestiges of Saxon estate boundaries which may, in turn, follow older territorial lines.

The most basic – and common – form of tumulus is the upturned dish shape of the bowl barrow (above), a burial mound that has adopted a consistent form throughout prehistory from the Neolithic on, even re-appearing in 6th century Saxon England as chieftains’ tombs. A simple barrow with a pleasingly rotund, roughly circular mound, usually surrounded by a ditch and an external bank, bowl barrows were built all over Britain, and most are between 5 and 40m across and up to 4m high.

The mounds of bell barrows (above) from the early Bronze Age on are separated from the ditch and bank that surrounds them by a narrow, level platform, or berm. They are most frequently associated with male burials and often contain daggers and other weapons among the grave goods. The ditch and platform can encompass up to four separate mounds, as can the ditch and bank of its refinement – the disc barrow (below) – which features a much smaller mound and wider platform.

While bell and disc forms are usually the graves of Bronze Age men, saucer barrows are predominately the tombs of women and can be recognized by a low, wide mound which extends without a berm to the ditch. Of the 60 in Britain, most are in Wessex, of the handful in Sussex, the best is at Chanctonbury Ring.

Of all the burial mounds, long barrows (below) are the oldest. There are around 300 of them in England and Scotland and a handful in Wales, all dating to the early Neolithic, contemporaries of the cromlechs and quoits of upland Britain. As the name suggests they are long – up to 125m – and they are usually the site of multiple interments. Their physical dominance of the landscape, and elaborate construction – some, like Belas Knap, Gloucestershire even have false entrances – inspired legends about their origin, the Wayland Smithy on the Berkshire Downs is a good example.

Grim’s Dykes

March 2013

Bokerley Dyke snaking its way southeast. The Saxons would have tried to invade from the left

March may be the official start of spring, a little warmer and with promises to keep, but it also hides a dark secret, for the month has martial connections. Named after Mars, the Roman god of war, it was not only the start of the Roman year, but also the month for mounting military campaigns. Those campaigns, and many more before and since, have left obvious marks on the countryside; battlefields, motte and baileys and castle keeps we would all recognise the names of, from Hadrian’s Wall to the half-mile-long magnificence of Maiden Castle in Dorset, with medieval and Tudor strongholds the length of the country between. The ubiquity of battle and war in every corner of Britain is evidence of the part that conflict has played in our history, but for every famous hillfort, castle and Roman wall, there are dozens of military connections hiding quietly in our countryside.

Among them, the miles of Iron Age Grim’s Dykes or Ditches that are common in Wessex and are believed to be territorial markers. Though not of a sufficient scale for military use – where they can still be tracked on the ground they tend to be of the scale of a modest railway embankment – the ditches have an etymological cousin in Graham’s Dyke, a local name for the Roman’s short-lived Antonine Wall across the Central Lowlands of Scotland. Grim was the Old English name for the Anglo-Saxon god of war, Woden, and other Grim’s Ditches, particularly the one at Colton, east of Leeds, may have been substantial enough to have a defensive use.

Compared to Offa’s Dyke – up to 65 feet at its widest and at least 64 miles long – Grim’s Dykes may seem modest. The eponymous creation of the eighth-century King of Mercia, Offa’s Dyke marks the English-Welsh border (running along Marches of a different kind) and is a potent symbol of tension throughout history. The dyke is built to have commanding views of Powys to the west, with the bank on the Mercian side and the ditch in front to deter any hapless invaders from Wales.

Seven-hundred years before Offa, at Wales’ northwestern horn, advancing Roman legions were confounded by both the treacherous Menai Straits and the Celtic tribes of Ynys Môn (Anglesey) on the other side. Roman Governor Agricola inflicted a punishing and conclusive triumph over them in 78 AD, and Ynys Môn was taken for good, but the memory of his brutal campaign is allegedly preserved in the names of fields; close to Brynsiencyn on the island, one howls its name as Cae-oer-waedd or the ‘Field of Bitter Lamentation’, another is simply “The Field of the Long Battle”.

Ridges and Bumps

February 2013

Strip Lynchets at Coombe Hill, Wooton-Under-Edge, Gloucestershire. Photo credit: Synwell / Foter.com / CC BY-NC-ND

As January passes into February, halfway from winter solstice to spring but still the coldest part of the year, it often feels as if it is a distinct season of its own. With low grass in the fields, a touch of frost or a light dusting of snow can reveal a swarm of slumbering lumps, bumps and hummocks of every form, suddenly apparent in a landscape sculpted by the long shadows of the low sun.

Despite appearances, many of these undulations, earthen ripples and waves across the landscape, are not defensive earthworks, ramparts or relics of long-forgotten battles, but evidence of our ancestors’ struggle with the land itself – the remains of various ancient methods of farming – while some are the outcome of nothing more violent than the gradual creep of soil down a hill, occasionally exacerbated by the frolicking trot of sheep.

The most marked features are those shown on Ordnance Survey maps as ‘Strip Lynchets’, the consequence of ploughing along the contours of slopes to create a flat area for crops, as practised in medieval and, occasionally, even earlier times. Dorset and Wiltshire have the best examples – below the Ridgeway near Bishopstone in North Wiltshire and near the village of Loders near Bridport, where giant stair-flights climb the slope; it’s not for nothing that ‘risers’ and ‘treads’ have crept into the terminology of strip lynchets to describe the relevant parts. Further north, at Conistone in Upper Wharfedale and Hall Garth, near Great Musgrave in Cumbria, the effect is gentler, but just as striking.

On more level ground, a pattern of regular undulation can reveal another medieval farming practice – ridge and furrow. Vast open fields were cultivated in furlong (literally furrow-long) strips by tenant subsistence farmers. Working clockwise around their strip, their ploughs turned the sod inward, building up a shallow ridge at the centre of their strip and leaving furrows along the long edges. Hauled by a team of eight oxen, the turning circle in the headland was difficult to achieve without curving slightly to the left at the end of each furlong and a shallow reverse-S or C form to the ridge can often be detected.

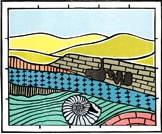

In the angular light cast on a February day, far subtler features can be discovered. Thin bands known as terracettes – but sometimes called catsteps or sheep tracks – are formed by soil creeping down steep slopes over the years, a result of repeated saturation and drying. Where bare sedimentary rock is exposed, a light fall of snow might pick out its bedding planes, revealing a succession of sea beds over millions of years or even, on red sandstones, the swash of a desert dune – a geological comfort for the middle of winter.

Park Pale

December 2012

Low embankment, mostly covered in bushes, in Chawton Park Wood. The pale is probably an old royal park boundary and it could run alongside the alignment of a Roman road. Link

A familiar label, a ‘park pale’ – as rendered in Old English blackletter on Ordnance Survey maps – marks the ditch and bank that formed the boundary of a medieval deer park. On the ground they might still define an area of woodland pasture, while banks several metres wide, once surmounted by a palisade or, perhaps, still carrying a stone wall, can be substantial even after centuries. The ditch that runs on the inside of the bank is usually less distinct. Their design allowed deer to bound into the park, but prevented them from leaping out again, making the deer park like a huge, terrestrial lobster pot, harvesting meat for the aristocratic table.

It’s a fitting feature to investigate during the season of high octane food, not least because in the low-fat, calorie-counted, gastronomically-tightfisted twenty-first century, Christmas dinner is the closest most of us get to a proper medieval banquet – a seasonal version of which was likely to include venison, while the most kindly of lords might give their servants deer offal – or numbles – for baking into a numble pie.

The model on which the ornamental parks of the eighteenth century were based, the medieval deer park is a landscape tradition whose roots extend back to the Norman conquest. William the Conqueror, who was crowned as an English monarch on Christmas Day, 1066, famously created 36 Royal Forests in the twenty-one years of his reign, reflecting his enthusiasm for the chase. At first, keeping and hunting deer was exclusively the reserve of royalty, but licenses from the King gave members of the aristocracy and senior churchmen the right to hunt on their own lands and a mania for creating deer parks took hold. The remains of one such park – first recorded in 1291, but almost certainly older – can be seen on the eastern side of Lyndhurst in the New Forest, where the pale is 9 metres wide and its bank over a metre high. Another park pale is associated with Kenilworth Castle and Pleasance – Henry V’s manor house in Warwickshire – while the most outstanding example in Scotland is at Fettercairn in Aberdeenshire, where eight miles of pale around the King’s Deer Park may even pre-date the Norman conquest of England.

The frequent occurrence of the park pale on modern maps is a reflection of their ubiquity in medieval landscapes; deer parks covered as much as 2% of England at the start of the fourteenth century and had a political importance to match. While there was no shortage of deer parks, there were shortages of deer because noble huntsmen were rather good at killing their trapped quarry, quicker than they could be re-stocked by hapless deer bounding over the pale. With his large Royal Forests, the King could send deer to his more co-operative and influential lords.